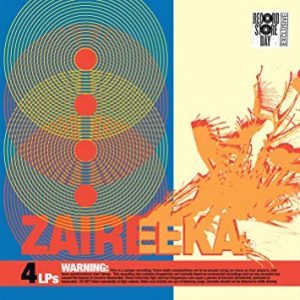

As an American rock band that came to known as much for their music as their experimentation, The Flaming Lips began their tryst with pushing the envelope with their 1997 album Zaireeka. The album consisted of four different CDs that were to be played simultaneously on four different CD players to make up one musical whole. Not just that, it came with a warning label that said: “This is a unique recording. These eight compositions are to be played using as many as four compact disc players and have synchronized start times. This recording also contains frequencies not normally heard on commercial recordings and on rare occasion has caused the listener to become disoriented”

As an American rock band that came to known as much for their music as their experimentation, The Flaming Lips began their tryst with pushing the envelope with their 1997 album Zaireeka. The album consisted of four different CDs that were to be played simultaneously on four different CD players to make up one musical whole. Not just that, it came with a warning label that said: “This is a unique recording. These eight compositions are to be played using as many as four compact disc players and have synchronized start times. This recording also contains frequencies not normally heard on commercial recordings and on rare occasion has caused the listener to become disoriented”

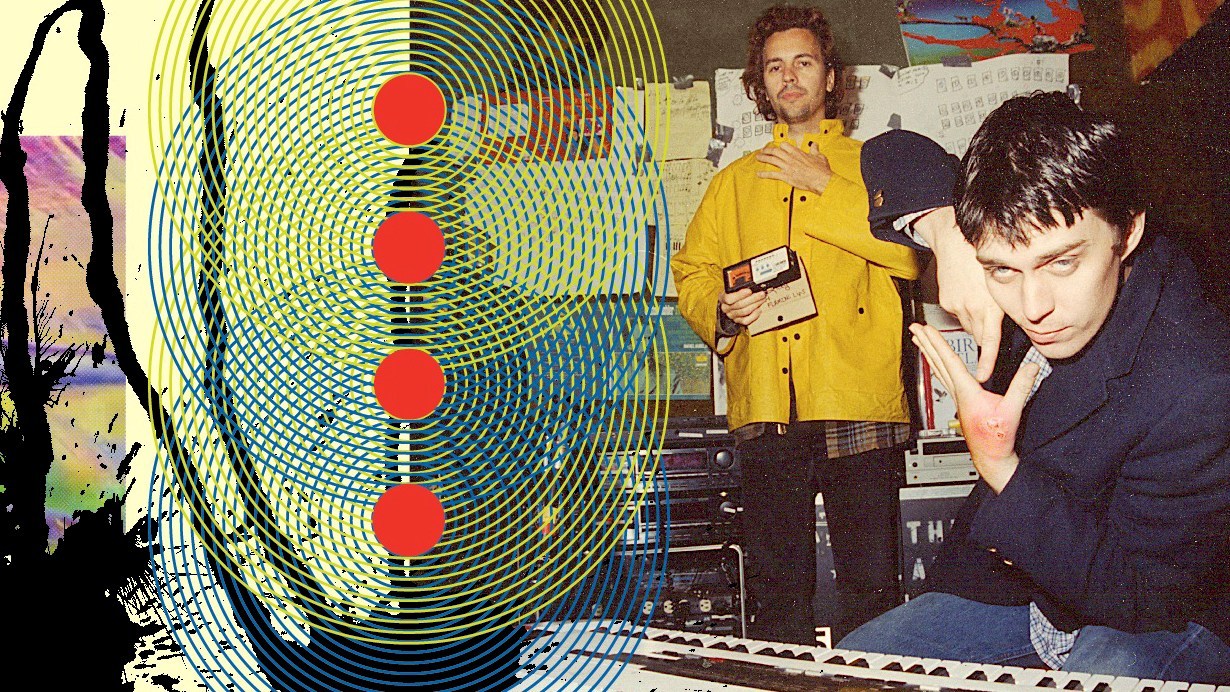

Hailed as the most groundbreaking experimental masterpiece released on a major label since Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music or the biggest troll job since Metal Machine Music, depending on whom you ask, the album was the first one the band released after the departure of their guitarist, Ronald Jones. The title of the album is a combination of the words Zaire and “Eureka” in a portmanteau that symbolized chaotic destruction and exciting discovery. The band was going through a phase of struggling to create songs until they began making sounds that would be split between four sources. This was a do-it-yourself approach of sorts to quadraphonic sound. The band scraped along their new sound trials with what they termed the “Parking Lot Experiments,” which involved Wayne Coyne and Steve Drozd recording music on cassettes. These were then to be played back simultaneously in a bunch of tape decks installed in automobiles parked in a lot by volunteers. With different speakers and sound systems entering the “mix”, the overall effect would be changed, and it would include some “conducting” by Coyne telling certain participants to alter the volume of their particular tape.

This self-indulgent and weird music energized the band and they came upon the idea to make a record that would be 100 CDs played at one time. Since this was the pre-mp3 era, commercially this wasn’t a viable idea. The Lips manager Scott Booker and Coyne’s bandmates eventually convinced the singer to bring down the conceived set of 100 CDs to 20, then 10 and eventually to the final four discs. Warner Bros. agreed to four CDs that would be played simultaneously on different CD systems with their own set of speakers. In order to secure financing for this experimental project, the Lips agreed to make both this set and their next record under the $200,000 that would normally be allotted for just one album.

In a sense, with regard to their sound, this was the end of the band’s identity as a rock band and the beginning of their time as a space-traveling psychedelic pop orchestra. The album began taking shape with harmonies, sonic counterpoints or reverberations that were divided between the different discs. The sounds were noisy, big and relied increasingly on spacey keyboards and affected vocals, which could be either abrasive or majestic. The lyrics veered to darker themes, reflecting the members’ tumultuous personal lives at the time, involving mental illness (“Riding to Work in the Year 2025”), a frustrating lack of comprehension (“Okay I’ll Admit That I Really Don’t Understand”) and an airline pilot who commits suicide mid-flight (“Thirty-Five Thousand Feet of Despair”). Another revelation of the band was the increased role of Drozd, who had long been the Lips’ secret weapon. Initially, he was just their drummer, but with Jones gone, he became the band’s multi-instrumentalist and arranger, shading in the blown-out soundscapes with keyboards and strings and horns and synths. It was a whole new sound for them — weird but veering towards being more grandly symphonic.

In a sense, with regard to their sound, this was the end of the band’s identity as a rock band and the beginning of their time as a space-traveling psychedelic pop orchestra. The album began taking shape with harmonies, sonic counterpoints or reverberations that were divided between the different discs. The sounds were noisy, big and relied increasingly on spacey keyboards and affected vocals, which could be either abrasive or majestic. The lyrics veered to darker themes, reflecting the members’ tumultuous personal lives at the time, involving mental illness (“Riding to Work in the Year 2025”), a frustrating lack of comprehension (“Okay I’ll Admit That I Really Don’t Understand”) and an airline pilot who commits suicide mid-flight (“Thirty-Five Thousand Feet of Despair”). Another revelation of the band was the increased role of Drozd, who had long been the Lips’ secret weapon. Initially, he was just their drummer, but with Jones gone, he became the band’s multi-instrumentalist and arranger, shading in the blown-out soundscapes with keyboards and strings and horns and synths. It was a whole new sound for them — weird but veering towards being more grandly symphonic.

With pre-orders totaling 14,000 (beating the break-even threshold), Zaireeka was released on Oct. 28, 1997. While their rabid fans were able to scrounge together four separate CD players to celebrate this sonic stunt, the music press was either amused, confused or angry about the concept, with Pitchfork famously giving Zaireeka a 0.0 rating for its impractical nature. Coyne spoke about the album is about the process of recording itself and getting the emotional reaction to the music that they were making. He envisioned the listening experience to be communal, social and collective. Zaireeka was considered to be a willfully difficult album. “Difficult” in the sense of dissonance, noise, and atonality, but also difficult to listen to logistically. In this age where new laptops don’t even have CD drives, the classic way of listening to it seems archaic. The album has since come out on vinyl, and you can find fan-edited one-disc mixdowns online. However, this leaves out the experience of locating four CD players to listen to it, with four hands to start them at the same time. And of course, this means that the music becomes progressively more out of sync over the course of one playthrough because of the fact that every CD player runs at a slightly different speed,.

Regardless of the debate over its merits, Zaireeka raised questions about why we consume music, when we consume music, how we consume music, and what we expect from our music. It was an album, a statement about the music and its consumption and conceptual art, all at the same time.